Essay:Cyberlaundering: Anonymous Digital Cash and Money Laundering

| Author(s) | Bortner, Mark |

| Published | 1996 |

This article will explore the latest technique in money laundering: Cyberlaundering by means of anonymous digital cash. Part I is a brief race through laundering history. Part II discusses how anonymous Ecash may facilitate money laundering on the Intenet. Part III examines the relationship between current money laundering law and cyberlaundering. Part IV addresses the underlying policy debate surrounding anonymous digital currency. Essentially, the balance between individual financial privacy rights and legitimate law enforcement interests. In conclusion, Part V raises a few unanswered societal questions and attempts to predict the future.

Disclaimer:

Although the author discusses this subject in a casual, rather than rigidly formal tone, money laundering is a serious issue which should not be taken lightly. As this article will show, fear of money laundering only serves to increase banking regulations which, in turn, affect everyone's ability to conduct convenient, efficient and relatively private financial transactions.

Part I Humble Beginnings

In the beginning, laundering money was a physical effort. The art of concealing the existence, the illegal source, or illegal application of income, and then disguising that income to make it appear legitimate[1] required that the launderer have the means to physically transport the hard cash.[2] The trick was, and still is, to avoid attracting unwanted attention, thus alerting the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) and other government agencies[3] involved in searching out ill-gotten gains.[4]

In what could be described as the "lo-tech" world of money laundering, the process of cleaning "dirty money" was limited by the creative ability to manipulate the physical world. Other than flying cash out of one country and depositing it in a foreign bank with less stringent banking laws,[5] bribing a bank teller, or discretely purchasing real or personal property, the classic approach was for a "smurf"[6] to deposit cash at a bank. Essentially, platoons of couriers assaulted the lobbies of banks throughout the United States with deposits under the $10,000 reporting limit as required under the Bank Secrecy Act.[7] The result was the formation of a serious loophole under the Bank Secrecy Act, allowing couriers almost limitless variables in depositing dirty money such as the number of banks, the number of branch offices, the number of teller stations at one branch office, the number of instruments purchased, the number of accounts at each bank, and the number of persons depositing the money.

In 1986, the Money Laundering Control Act (the Act)[8] attempted to close the loopholes in the prior law that allowed for the structuring of transactions to flourish.[9] In criminalizing the structuring of transactions to avoid reporting requirements, Congress attempted to "hit criminals right where they bruise: in the pocketbook."[10] Under the Act, the filing of a currency transaction report (CTR)[11] is required even if a bank employee "has knowledge" of any attempted structuring.[12] Thus, it appeared as if the ability to launder the profits from illegal activity would be severely hampered.

As the physical world of money laundering began to erode, the tendency to use electronic transfers to avoid detection gained a loyal following. Electronic transfers of funds are known as wire transfers.[13] Wire transfer systems allow criminal organizations, as well as legitimate businesses and individual banking customers, to enjoy a swift and nearly risk free conduit for moving money between countries.[14] Considering that an estimated 700,000 wire transfers occur daily in the United States, moving well over $2 trillion, illicit wire transfers are easily hidden.[15] Federal agencies estimate that as much as $300 billion is laundered annually, worldwide.[16] As the mountain of stored, computerized information regarding these transfers reaches for the virtual stars above, the ability to successfully launder increases as the workload of investigators increases.[17]

Although wire transfers currently provide only limited information regarding the parties involved,[18] the growing trend is for greater detail to be recorded.[19] If the privacy of wire transfers is compromised, due to burdensomely detailed record keeping regulations,[20] electronic surveillance of transfers, or other potentially invasionary[sic] tactics,[21] then the leap from the physical to the virtual world will be nearly complete. If laundering is to survive it must expand its approach, entering the world of cyberspace.

While change is often a frighteningly awkward experience, for an enterprising criminal operation, that wishes to remain open for business, it is a necessity. As the above mentioned race through laundering history demonstrates, creativity, and not necessarily greed, has been the launderer's salvation. The recent explosion of Internet access[22] may be the new type of detergent which allows for cleaner laundry.

Part II Enter, Anonymous Ecash

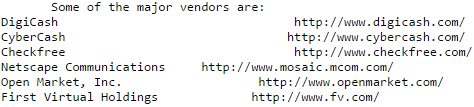

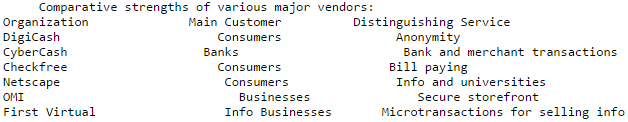

In the virtual universe of cyberspace the demand for efficient consumer transactions has lead to the establishment of electronic cash.[23] Electronic cash, or digital money, is an electronic replacement for cash.[24] Digital cash has been defined as a series of numbers that have an intrinsic value in some form of currency.[25] Using digital cash, actual assets are transferred through digital communications in the form of individually identified representations of bills and coins - similar to serial numbers on hard currency.[26][27] While the ultimate goal of each vendor is to facilitate transactional efficiency, bolster purchasing power on the Internet, and, of course, earn substantial profit in a new area of commerce, each vendor plays by slightly different rules.[28] Although the intricacies of individual vendors are quite fascinating, for the purpose of this article, it is fair to say that all but one vendor have one trait in common: lack of anonymity.

The exception to the general rule of lack of anonymity is DigiCash.[29] Digicash is an Amsterdam-based company created by David Chaum,[30] a well respected cryptologist. DigiCash's contribution to Internet commerce is an online payment product called "ecash."[31] According to DigiCash, electronic cash by DigiCash "combines computerized convenience with security and privacy that improve on paper cash."[32] Ecash is designed for secure payments from any personal computer to any other workstation, over e-mail or Internet.[33] In providing security and privacy for its customers, DigiCash uses public key digital blind signature techniques.[34] Ecash, unlike even paper cash, is unconditionally untraceable. The "blinding" carried out by the user's own device makes it impossible for anyone to link payment to payer. But users can prove unequivocally that they did or did not make a particular payment, without revealing anything more.[35] While ecash's security technology may be among the best in the business as of this writing, the focus of this article is upon one aspect of DigiCash that is of particular interest to money launderers and law enforcement: Anonymity.

Part III The Money Laundering Control Act and Anonymous Laundering

This section examines how the Amendments to the Bank Secrecy Act of 1970, commonly referred to as the Money Laundering Control Act of 1986,36 apply to cyberspace and cyberlaundering. Without delving into the actual techniques involved in using public keys, blind signatures or any other encryption or decryption device, the best way to explain how anonymous digital cash could benefit money launderers' is by example. The following example will be used to demonstrate the law's application.

Doug Drug Dealer is the CEO of an ongoing narcotics corporation. Doug has rooms filled with hard currency which is the profits from his illegal enterprise. This currency needs to enter into the legitimate, mainstream economy so that Doug can either purchase needed supplies and employees, purchase real or personal property or even draw interest on these ill-gotten gains. Of course, this could be accomplished without a bank account, but efficiency demands legality. Anyhow, Doug employs Linda Launderer to wash this dirty money. Linda hires couriers ("smurfs") to deposit funds under different names in amounts between $7500 and $8500 at branches of every bank in certain cities. This operation is repeated twice a week for as long as is required. In the meantime, Linda Launderer has been transferring these same funds from each branch, making withdrawals only once a week, and depositing the money with Internet banks that accept ecash. To be safe, Linda has these transfers limited to a maximum of $8200 each. Once the hard currency has been converted into digital ecash, the illegally earned money has become virtually untraceable; anonymous. Doug Drug Dealer now has access to legitimate electronic cash.

Doug Drug Dealer is, of course, likely to be found guilty of more than just participating in a money laundering scheme. However, how the law applies to Linda Launderer and the Internet banks is more confusing. The purpose of the 1986 Act was to specifically criminalize the structuring of transactions so as to avoid the reporting requirements.37 Linda and her army of couriers are almost certainly violating structuring regulations by depositing small amounts in regular bank accounts.38 The problem is how to apply current money laundering law to cyberlaundering.

In the scenario above, Linda Launderer transfers sums of money less than $10,000 from non-Internet bank accounts to Internet-based ecash accounts. If the Internet bank is FDIC insured,39 as Mark Twain Bank40 then federal depository regulations may apply. However, the cyberbank will not automatically be required to file a CTR regarding these transactions as all are under the $10,000 filing requirement. Nevertheless, if any employee of the Internet bank has even a suspicion of structuring,41 a CTR may be filed.42 As in the tangible banking world, the information contained on a CTR is only as insightful as the information presented by the bank conducting the prior transaction.43 In essence, each record in the chain of transfers is only as strong as the previous recordation.

The catch is that Linda Launderer's transfer was deposited into an ecash account. According to one cyberbank which currently accepts ecash,44 ecash accounts are not FDIC insured.45 A lack of federal insurance protection is understandable for the reason that digital money is currently created by private vendors, rather than the Federal Reserve.46 Thus, digital cash does not enter into the marketplace of hard currency thereby affecting monetary supply or policy, yet.

Since Linda Launderer's transfer was deposited into a non-FDIC insured, and thus, presumably non-federally regulated account, then there should be no mandatory compliance with the filing regulations contained within the Money Laundering Control Act of 1986. If these assumptions prove correct, whether digital money is anonymous or not will be of less relevance to money launderers and law enforcement. If certain cyberbanks, or even specific non-FDIC currency accounts within a cyberbank are able to operate outside the reach of current federal regulations, laundering on the Web may become one of the most rapidly expanding growth industries. It should be remembered that a criminal organization desires to clean its dirty money, not necessarily protect their deposits from institutional banking failures.

Once the ecash account has been established, digital funds can be accessed from any computer that is properly connected to the Intenet. A truly creative, if not paranoid, launderer could access funds via telnet.47 Telnet is a basic command that involves the protocol for connecting to another computer on the Internet.48 Thus, Linda Launderer could transfer illegally earned funds from her laptop on the Pacific Island of Vanuatu, telneting to her account leased from any unknowing Internet Service Provider49 in the United States and have her leased Internet account actually call the bank to transfer the funds, thus concealing her true identity. This would, of course, leave an even longer trail for law enforcement to follow. Anyhow, ecash, being completely anonymous, allows the account holder total privacy to make Internet transactions. Thus, the bank holding the digital cash, as well as any seller which accepts ecash, has virtually no means of identifying the purchaser. Therefore, the combination of anonymous ecash and the availability of telnet may give a launderer enough of a head start to evade law enforcement, for the moment.

In the world of earth and soil, money can be laundered by the purchase of real and personal property. However, any cash transaction over $10,000 is subject to a transaction filing requirement.50 Real estate agents and automobile dealers, to name a few, are prime targets for the deposit of large sums of cash. In fact, such agents and dealers have been indicted for allowing drug money to be used to purchase expensive property.51

On the Internet, anonymous ecash would allow for anonymous purchases of real and personal property. This fact yields at least two separate, but interrelated problems. First, the launderer or drug dealer will be able to discretely use illegally obtained profits to legitimately purchase property. However, currently, the opportunity to spend thousands of dollars of digital money, or ecash for that matter, on the Internet is virtually nonexistent.52 Second, the temptation for automobile and real property dealers to become players in the game for anonymous ecash seems overwhelming. If a seller or dealer understands that it can not possibly trace who spent ecash at its establishment, the fear of becoming involved with dirty money is drastically reduced.53 Under current law, a seller of property must file a CTR for any cash transaction over $10,000.54 If the purchaser's identity is anonymous, and even the bank can not trace the spent ecash, the force of the Money Laundering Control Act of 1986 is withered into mere words on a page. Of course, Congress could attempt to legislate in this new area of commerce.

Obviously, transferring hard currency to ecash and then spending the ecash is an appealing opportunity to potential launderers'. What if the ecash is then transferred back to a regular hard currency account? This may seem a foolish act as the entire purpose is to reap the benefits of anonymous ecash. However, presently, there are no opportunities to purchase automobiles or real property by the exclusive use of anonymous ecash. Thus, the desire to convert private and untraceable ecash into a more functional means of purchasing is understandable.

Whether a regular, non-Internet currency account already exists or must be created to deposit the transferred ecash into may be irrelevant. Filing a CTR would be a legal necessity if the transfer amount is over the $10,000 reporting limit, as the transfer will deposit hard currency in a tangible, institutionalized, and regulated bank account. A transfer from completely anonymous ecash to hard currency might alert law enforcement as to the existence of the ecash account. While this alone would not track down laundered money, it might put a suspicious agent on notice.

In summary, Linda Launderer has knowingly structured financial transactions so as to avoid reporting requirements. Under current law she is in violation of The Money Laundering Control Act of 1986. However, if the cyberbanks in which she has ecash deposits are outside the reach of current banking regulations, these banks have no duty to file any currency transaction reports. Nevertheless, assuming that cyberbanks which accept anonymous ecash are somehow subject to the same laws and regulations which financial institutions in the tangible world are, Linda must first be caught before she can be found guilty. This is where anonymous ecash may save Linda from fines and jail time.55 Even if cyberbanks are required to file transactional reports pertaining to ecash, the reports will be virtually useless, as the banks have no knowledge as to which funds are Linda's. Thus, Linda, our overly creative launderer, and Doug, our devious drug dealer, may enjoy the benefits of completely anonymous money laundering. That is, unless Congress decides to attempt legislation in the area of digital money and virtual banking, or FinCen is somehow granted the constitutional authority to secretly monitor all cyberbanking transactions, despite its lack of accountability to the general population.

Endnotes

These are essential to fully understand the article!

- ↑ For a good background on money laundering see Sarah N. Welling, Comment, Smurfs, Money Laundering and the Federal Criminal Law, 41 Fla. L. Rev. 287, 290 (1989).

- ↑ In this article, "hard cash or currency" refers to any non-Internet-based money. As an illustration of hard cash, a suitcase filled with $1million worth of $20 bills weighs more than 100 lbs. See Business Week, Money Laundering, March 18, 1985.

- ↑ The United States Department of the Treasury has created a technology-based law enforcement unit called Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FinCen). FinCen has been delegated the job of oveerseeing[sic] and implementing policies to prevent and detect money laundering. See FinCen at URL: http://www.ustreas.gov/treasury/bureaus/fincen.facts.html.

- ↑ While the profits from sales of illegal narcotics is the most common and widely publicized example of "dirty money," the gains from illegal gambling, prostitution, extortion, and essentially any illegal activity are a suspect classification. See H.R. Rep. No. 975, 91st Cong., 2d Sess. 11, reprinted in 1970 Code Cong. & Admin. News 4394, 4396.

- ↑ Traditional non-U.S. hotspots for laundering include, but are not limited to, Switzerland, Panama, Bahamian Islands and Luxembourg. However, recently, even the Swiss have been turning away deposits from suspected illegal gains. See Swiss bankers changing rules, St. Pete. Times, Oct. 10, 1995, at 17A & 24A.

- ↑ Courriers[sic] who scurry from bank to bank to conduct multiple cash transactions under the $10,000 reporting limit. The name "smurf" is from the hyperactive blue cartoon characters that seemed to be everywhere at once.

- ↑ 31 C.F.R. sect. 103.22(a)(1) (requirement that a currency transaction report (CTR) be filed for "transactions" of more than $10,000). The Bank Secrecy Act itself is contained at 18 U.S.C. sects. 1956-1957 (1970). It incorporates related statutes such as 31 C.F.R. sect. 103.22.

- ↑ Money Laundering Control Act of 1986, Pub. L. No. 99-570, Title I, Subtitle H, sects. 1351-67, 100 Stat. 3207-18 & 3207-39 (1986) (codified as amended at 18 U.S.C. sects. 1956-1957 (1988 & Supp. V 1993)).

- ↑ 18 U.S.C. sect. 1956(a)(1) criminalizes structuring and attempted structuring of financial transactions so as to avoid reporting requirements. The reporting requirements are set forth in 31 C.F.R. sect. 103.22.

- ↑ H.R. Rep. No. 855, 99th Cong., 2d Sess. 13 (1986).

- ↑ A CTR is a transactional report which may include the date and time of the transaction, the amount involved and certain information regarding the identity of the originator and the beneficiary of the transaction. See 31 U.S.C. sect. 5313 (1988); 31 C.F.R. sect. 103.22 (1988).

- ↑ 18 U.S.C. sect. 1956(a) (based upon the text, actual subjective knowledge that the money used in the transaction was derived from an unlawful source, rather than what should have been known is the standard to be applied). See 31 C.F.R. sect. 103.22(a)(1) (1988) ("Has knowledge" is defined as pertaining to that of a partner, director, officer or employee of a financial institution or on the part of any existing system at the institution that permits it to aggregate transactions).

- ↑ A wire transfer is simply the transfer of funds by electronic messages between banks. U.C.C. Article 4A Prefatory Note (1991) defines a wire transfer as "a series of transactions, beginning with the originator's payment order, made for the purpose of making payment to the beneficiary of the order."

- ↑ There are three major electronic funds transfer systems: (1) SWIFT: the Society for Worldwide Interbank Financial Telecommunication, is a Belgian-based association of banks that provides the communications network for a large number of international funds transfers, as well as intracountry transfers within the United States; (2) CHIPS: the Clearing House Interbank Payments System, is a funds settlement system operated by the New York Clearing House; and (3) Fedwire: the funds transfer system operated exclusively by the Federal Reserve System.

- ↑ See Office of Technology Assessment, Congress of the United States, Information Technology for the Control of Money Laundering, iii (1995) (OTA-ITC-630).

- ↑ Id. at 2.

- ↑ In 1994, the number of CTRs was approximately 10,765,000. The IRS, who is in charge of checking on suspicious transactions, does not have enough investigators to consistently check these reports. However, FinCen, in its desire to keep the IRS up to speed, is currently attempting to process every CTR by means of its artificialintelligence[sic] system. See Id. at 6-7.

- ↑ See supra note 11 for a brief explanation of the limited contents of a CTR.

- ↑ As a result of the Money laundering Suppression Act of 1994, an additional form will be required for suspect transfers. If it currently cost a bank between $3 to $15 to file a CTR, the cost will only increase as additional forms are required. See Office of Technology Assessment, supra note 15 at 7.

- ↑ In addition to the information contained on a CTR, a financial institution may be required to retain either the original or a copy of both sides of the monetary instrument for a period of five years. 31 C.F.R. sect. 103.38.

- ↑ "Using evidence from the first court-ordered wiretap on a computer network, federal agents have charged an Argentine student with hacking his way into the U.S. military and NASA computers." WiretapSnares Hacker Who Raided Defense Net, Chicago Trib., March 29, 1996, at 1. (This could just as easily be performed on wire transfer system).

- ↑ Twenty-five million Americans had Internet access in early 1995. See Legal Issues in the World of Digital Cash, available online at URL: http://www.info-nation.com/cashlaw.html/.

- ↑ Electronic Cash, digital cash, digital currency and cybercurrency are synonyms for an electronic medium of exchange which has no intrinsic value, and the barest trace of physical existence. See Daniel C. Lynch & Leslie Lundquist, Digital Money: the new area of Internet commerce, 1996 at 99.

- ↑ Id. at 99.

- ↑ David Cline, Term Paper, Cryptographic Protocols for Digital Cash, George Washington University, School of Engineering and Applied Science (Computer Security I). Available online at URL: http://www.seas.gwu.edu/student/clinedav/.

- ↑ Information Infrastructure Task Force, The Report of the Working Group on Intellectual Property Rights, Intellectual Property on the National Information Infrastructure, 193 (Sept. 1995). Available online at URL: http://www.uspto.gov/web/ipnii (PDF format); and URL: gopher://ntian1.ntia.doc.gov:70/00/papers/documents/files/ipnii.txt (ASCII format).

Citenote missing in original document

- ↑ See Lynch & Lundquist, supra note 23 at 24, table 2.1.

- ↑ See Lynch & Lundquist, supra note 23 at 37, table 2.2.

- ↑ Digicash homepage. Available online at URL: http://www.digicash.com/.

- ↑ For more information on David Chaum see the following web sites: URL: http://www.digicash.com/digicash/people/david.html/; URL: http://www.mediamatic.nl/whoiswho/Chaum?DavidChaum.html/; URL: http://www.mif.se/NetCash.html/.

- ↑ "Ecash" is the exclusive brand of digital money created by Digicash. Although ecash and electronic cash are virtually synonymous, ecash is a brand name while electronic cash is a general term used to identify digital currency. See URL: http://www.digicash.com/ecash/ecash-home/html/.

- ↑ See URL: http://www.digicash.nl/publish/digibro.html/.

- ↑ See URL: http://www.digicash.nl/ecash/about.html/.

- ↑ For an overview of DigiCash's cryptographic and blind signature techniques see URL: http://www.digicash.nl/ecash/about.html; URL: http://www.digicash.nl/ecash/aboutsecurity.html; URL: http://www.digicash.com/publish/sciam.html.

On the other hand, blind signatures restore the privacy lost in regular digital signatures. Before sending a note number to the bank for signing, the sender multiplies it by a random factor. The bank knows nothing about what it is signing except that it carries the sender's digital signature. After receiving the blinded note signed by the bank, the sender/bank customer divides out the blinding factor and uses the note as anonymous digital cash. Because the bank has no idea of the blinding factor, it has no way of linking the note numbers to the account holder's identity. This anonymity is limited only by the unpredictability of the creator's numbers. - ↑ A user always has the option to reveal itself when using ecash. For a more indepth look at ecash security see DigiCash at URL: http://www.digicash.com/publish/digibro.html/; URL: http://www.digicash.com/publish/sciam.html/. See also Lynch & Lundquist, supra note 23 at 114.